An Introduction to Modern Police Firearms

by Duke Roberts and Allen P. Bristow

I purchased this textbook for 50 cents at a college library book sale. The distinctive smell of a vintage library book adds to the nostalgic appeal. The book was published in 1969 during the Adam-12 era. This was about 20 years before American police departments made the switch from revolvers to semiautomatic pistols, although the book covers both. There is a chapter on the police shotgun, but nothing about rifles. Other topics include safety, maintenance, ballistics, marksmanship, chemical agents, the legal and ethical use of firearms, and sample Use of Deadly Force policies.

Nomenclature and Ballistics

“Located within the barrel is the rifling, which consists of grooves cut in a spiral manner the length of the bore. The bore is the inside portion of the barrel… When the bullet travels down the bore, rifling imparts a spin to it. The bullet rotates in the air, developing what is called gyrostatic stability, which greatly increases its accuracy.”

“Cartridges are designated in the United States by the diameter of the bullet. For example, a cartridge whose bullet is 22/100 of an inch in diameter is called a .22 caliber cartridge. The .45 caliber pistol shoots a bullet which is 45/100 of an inch in diameter. This method of cartridge designation is not completely accurate, however, and if the student applies a micrometer to most of the standard cartridge cases and bullets, he will find they vary somewhat from the numerical designation. For example, the .38 Smith & Wesson Special bullet is actually .357 of an inch in diameter.”

“When one hears the report from the firing of a revolver, he is not hearing the exploding gun powder, as is commonly thought. He is hearing, instead, the air-wave sound-cone and vacuum slap. In addition, some portions of the burning gas and powder will flash into the air behind the bullet. This is called muzzle flash.”

Basic Marksmanship

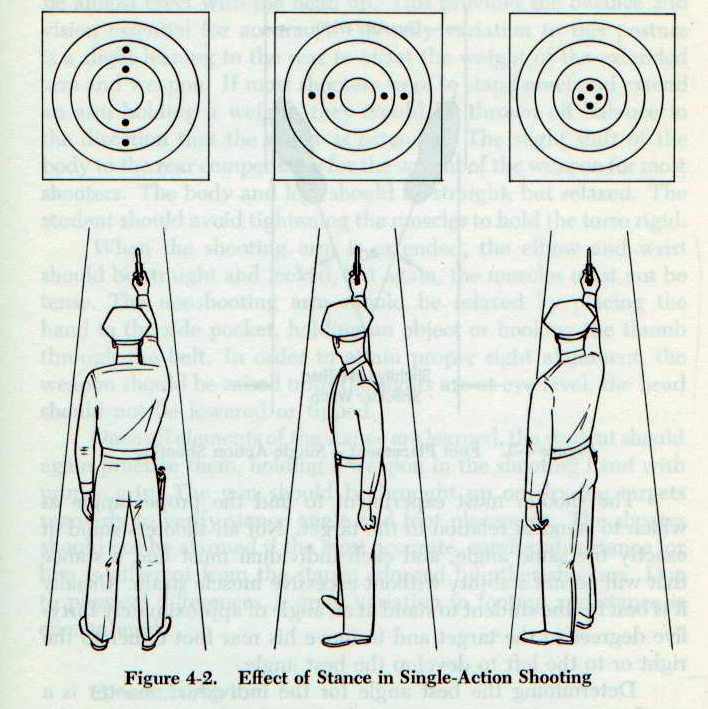

“Once the correct grip has been mastered, the student is ready to learn the proper stance. The first consideration is the angle of the stance or the direction in which the shooter is facing. The student who begins by facing the target directly will find that he has difficulty controlling the elevation of his shots and will have a tendency to rock back and forth because he is not braced against such motion. If the student shooter stands at a ninety degree angle to the target, he will not have trouble with the elevation of the shots on the target, but he will probably find that the shorts spread from right to left.”

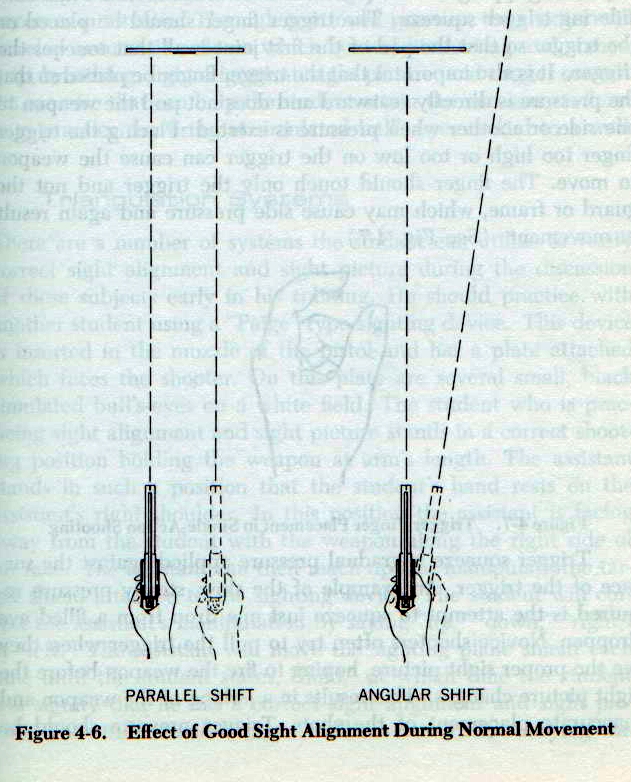

“There are two kinds of error possible during sighting. The first, called lateral error, occurs when the sights are perfectly aligned but are not pointed at the target. This may be caused by a slight movement of the body parallel to the line of fire. This error is not cumulative. If the body moves two inches, the shot will be off by two inches.

The second type of error is an angular error. It is caused by not having the sights in proper alignment. The magnitude of error is dependent on both size of the angle (formed by the gun barrel and the line of sight) and the distance of the shooter from the target. For instance, if the angle was such that the shot would be one inch off target at a distance of one foot, at 120 feet, the shot would miss by ten feet. For a more practical example, consider an error in alignment of 1/16 of an inch for a gun barrel length of eight inches. At a distance of twenty-five yards, the bullet will miss by seven inches. This represents an angular error of a little less than one-half degree. Obviously, in terms of accuracy, angular errors are much more serious than lateral errors.”

“The student’s shots may be on the target, in a group, or scattered over the target. If the shots are scattered it indicates the he is not uniformly practicing one or more of the fundamentals of marksmanship… Once the student is able to shoot a group, recognizable as a cluster of shots striking the same area, the instructor can assist him in correcting the error that causes the group to miss the bull’s-eye, or in correcting the sights if they are not properly adjusted.”

“Observers calling shot location on targets may say, for example ‘That is nine at six o’clock.’ The student then knows the bullet struck the nine ring low.”

Combat Shooting

“Combat shooting techniques include double-action shooting and the development of proficiency from protective positions… The correct stance in double-action shooting is any position in which the police officer presents the minimum target area to the opponent… In almost all actual situations, the suspect will be moving and will not provide an easy target for a deliberate, single-action shot.”

“In a combat situation… the decision to shoot is almost instantaneous, and if the officer does draw his weapon and fire, the chances are that he will probably not see his sights at all. He will be involved in what is called instinct or snap shooting, will be keeping his eyes on the suspect, and will probably rely on several shots double action.”

“The primary reasons for assuming a protective position in combat shooting are to reduce the exposed area of the officer and to provide the steadiest possible shooting position. If he can support his arm while firing, thus steadying his aim, the officer will increase the probability of hitting the suspect.”

“Some shooters prefer to hold the revolver with two hands and argue that their instinctive shooting is more accurate. While this may be true, it is dangerous to condition the shooter to the use of both hands during instinctive double-action firing. In a combat situation, he may be holding a flashlight, or his hand may be otherwise occupied.”

“Because most police gun fights occur at night, it is ridiculous to concentrate all of the training during the day. Modified combat courses should be fired at night where the officer is required to shoot his service revolver at silhouette targets in darkness, illuminating the target with his flashlight. In some forward-thinking police departments half of their combat-course practice is conducted at night.”

Selecting a Weapon

“Unless otherwise specified by the department’s regulations, the four-inch barrel is by far the most satisfactory for the service revolver. The increased sight-radius and bullet velocity provided by the six-inch barrel are of negligible importance when ease of carrying, maneuverability and on-duty or off-duty use are considered.”

“As the velocity and the bullet size, or weight, is increased, so is the recoil of the weapon. The police officer should avoid ‘over-gunning’ himself with respect to caliber selection if he cannot master the more difficult caliber.”

“The primary purpose of the exterior finish on the handgun is to protect it from rust and corrosion. Typical finishes include bluing, Parkerizing, nickel and chromium plating, and most recently, the stainless steel finish. The police officer should choose between the blue or parkerized finish for his on-duty weapon. These finishes protect the weapon adequately from rust and do not create any reflection which can affect the officer’s sighting of the weapon, or which could attract attention to him in darkness during a gun fight.”

The Police Shotgun

“The police shotgun is a 12 gauge weapon. The word ‘gauge’ describes the inside barrel diameter of a shotgun as the term ‘caliber’ does a rifle or pistol. When we describe a rifle or a pistol by caliber, we refer to the diameter of the bore in hundredths of an inch (for example, .22, .38, or .45). If we followed the same system for shotguns, the 12 gauge shotgun would be a .729 caliber weapon. However, we refer to the shotgun by its traditional designation which is the gauge.”

“When the slide handle is pulled to the rear, the action of the shotgun is opened. When the slide handle is pushed to the front, the action and breech close, loading a shell into the chamber… As the shot leaves the muzzle, it begins to spread into what is called its ‘pattern.’”

“One cannot deny that there is recoil from the shotgun, but if the weapon is properly held, and if the shooter is standing properly, the recoil is negligible. The shotgun butt should be mounted to the shoulder with the cheek resting lightly against the stock. The shooter grips the weapon firmly, holding it well into the shoulder.”

Chemical Agents

“Chemical agents [such as tear gas] may be delivered over greater distances than the thrown grenade by use of projectiles. These projectiles are fired from a thirty-seven millimeter gas gun.”

Hostages

“Agreeing to surrender one’s weapon or oneself to a suspect holding a hostage gives the suspect an additional weapon and an addition hostage, thus complicating the decision for the next police officer encountering the suspect. Generally, a police officer should never go farther than permitting a suspect with a hostage to escape; he should retain his weapon and seek cover and concealment, agreeing not to shoot at the suspect, but never giving the suspect an opportunity to obtain additional weapons and hostages.”

Criminal and Civil Liability

“Never draw a weapon unless there is probable cause to believe you may have to use it.”

“It is not enough to be legally correct and ethically proper or to establish a civil defense, because in the hands of a jury, civil liability is frequently determined on a basis of ability of the plaintiff to pay, social and racial pressures, or mistrust and disrespect for law enforcement officers.”

Appendix A lists the recommendations of the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, 1967.

“It is essential that all departments formulate written firearms policies which clearly limit their use to situations of strong and compelling need. A department should even place greater restrictions on their use than is legally required. Careful review of the comprehensive firearms’ use polices of several departments indicate that these guidelines should control firearms use:

- Deadly force should be restricted to the apprehension of perpetrators who in the course of their crime threatened the use of deadly force, or if the officer believes there is a substantial risk that the person whose arrest is sought will cause death of serious bodily harm if his apprehension is delayed. The use of firearms should be flatly prohibited in the apprehension of misdemeanants, since the value of human life far outweighs the gravity of a misdemeanor.

- Deadly force should never be used on mere suspicion that a crime, no matter how serious, was committed or that the person being pursued committed the crime. An officer should either have witnessed the crime or should have sufficient information to know, as a virtual certainty, that the suspect committed an offense for which the use of deadly force is permissible.

- Officers should not be permitted to fire on felony suspects when lesser force could be used; when the officer believes that the suspect can be apprehended reasonably soon thereafter without the use of deadly force; or when there is any substantial danger to innocent bystanders. Although the requirement of using lesser forces, when possible, is a legal rule, the other limitations are based on sound public policy. To risk the life of innocent persons for the purpose of apprehending a felon cannot be justified.

- Officers should never use warning shots for any purpose. Warning shots endanger the lives of bystanders, and in addition, may prompt a suspect to return the fire. Further, officers should never fire from a moving vehicle.

- Officers should be allowed to use any necessary force, including deadly force, to protect themselves or other persons from death or serious injury. In such cases, it is immaterial whether the attacker has committed a serious felony, a misdemeanor, or any crime at all.

- In order to enforce firearms use policies, department regulations should require a detailed written report on all discharges of firearms. All cases be thoroughly investigated to determine whether the use of firearms was justified under the circumstances.

If all departments formulated firearms use policies which include the above principles and these policies are consistently enforced, many of the tragic incidents which had a direct bearing upon community relations could have been avoided.”

Appendix B includes examples of regulations on the use of firearms and deadly force from several police departments, including Rochester, New York; Detroit, Michigan; Downey, California; and Miami, Florida.

Roberts, Duke, and Allen P. Bristow. Essay. In An Introduction to Modern Police Firearms. Beverly Hills, California: Glencoe Press, 1969. Buy from Amazon.com

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Discover more from The Key Point

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.