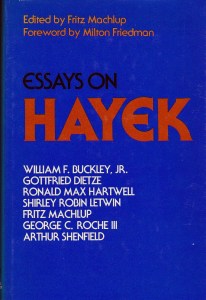

Essays on Hayek

Edited by Fritz Machlup

Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992) received the Nobel Prize in Economics on December 11, 1974 for his theory of business cycles and the effects of monetary and credit policies. The following year, the Mont Pelerin Society held a conference at Hillsdale College covering various aspects of Hayek’s work. This book is a collection of the papers presented and discussed.

I find it noteworthy that Hayek wrote The Road to Serfdom (1944) on the consequences of socialism in the same era that George Orwell wrote Animal Farm (1945) and 1984 (1949).

George C. Roche III – Freedom and Responsibility

“Can self-government exist divorced from what the American founding fathers called civic virtue?”

“The free society requires a competitive market economy. But it also requires an institutional and moral framework which provides the individual with his moral bearings, with a sense of freedom and responsibility. These elements, coupled with a properly limited government, constitute the preconditions for what Friedrich Hayek has described as the Rule of Law.”

Hayek argues that collectivism destroys the ethics of individuals.

Gottfried Dietze – Rule of Law

“While freedom is under the law, the law is not superior to freedom… for law is merely a means which has the protection of freedom as its end… For Hayek, then, the rule of law is inseparable from freedom.”

“For Hayek the rule of law is the opposite of the rule of men… In that order, all men in society—subjects as well as rulers—are bound by the rule of law.”

“In The Constitution of Liberty Hayek devotes a chapter to Responsibility and Freedom, writing: ‘Liberty and responsibility are inseparable. A free society will not function or maintain itself unless its members regard it as right that each individual occupy the position that results from his action and accept it as due to his own action.”

“While responsibility ‘means an unceasing task, a discipline that man must impose upon himself if he is to achieve his aims,’ it also implies responsibility toward others. It means obedience to the laws.”

“‘Order is an indispensable concept… We cannot do without it.’”

“Hayek laments that during the last generations, private law has been increasingly replaced by public law, the former aiding, the latter threatening, liberty. Yet he does not urge disobedience to public law.”

The terms private law and public law were new to me. Private law includes contract law, property law, and tort law—laws that regulate interactions between private persons and businesses. Public law includes constitutional law, criminal law, international law—laws that regulate government interactions with persons and businesses.

Fritz Machlup – Division of Knowledge

“One of the most original and most important ideas advanced by Hayek is the role of the ‘division of knowledge’ in economic society.”

“What matters in this connection is not scientific knowledge but the unorganized ‘knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place’; practically every individual ‘possesses unique information of which beneficial use might be made’, but which ‘cannot be conveyed to any central authority in statistical form… Central Planning… cannot take direct account of these circumstances of time and place’ and ‘decisions depending on them’ must be ‘left to the man on the spot… We need decentralization because only thus can we [ensure] that the knowledge of the particular circumstances… will be promptly used.’”

In other words, “information in the minds of millions of people is not available to any central body or any group of decision-makers who have to determine prices, employment, production, and investment but do not have the signals provided by a competitive market mechanism.”

“Fundamentally, in a system in which the knowledge of the relevant facts is dispersed among many people, prices can act to coordinate the separate actions of different people.’ The price system is ‘a mechanism for communicating information’ and ‘the most significant fact about this system is the economy of knowledge with which it operates.’ The problem is not that a unique solution could be derived from a complete set of ‘data,’ but that ‘we must show how a solution is produced by the interaction of people each of whom possesses only partial knowledge.’”

This section reminds me of system thinking. Although he doesn’t use these terms, Hayek is describing markets as complex systems—in which results emerge from the interactions of autonomous agents—as opposed to a complicated system which can be designed and controlled with predictable results.

“He criticizes modern micro-economic theory, especially the theories of the firm and of the industry, for their preoccupation with static analysis of models of pure and perfect competition and for their scant attention to competition as a dynamic process.”

“The fundamental thesis of Hayek’s theory of the business cycle was that monetary factors cause the cycle but real phenomena constitute it.” In a nutshell, whereas John Maynard Keynes advocated government intervention to manage economic down cycles, Hayek argued that this prolonged the pain and it was better to let the economy self-correct. A contemporary case in point may be the inflation resulting from prolonged stimulative monetary policy (zero interest rate policy and quantitative easing) and fiscal policy (massive deficit spending ballooning the national debt).

Arthur Shenfield – Scientism

“Scientism is the uncritical application of the methods, or of the supposed methods, of the natural sciences to problems for which they are not apt. In the present context it is their application to problems of human society.”

“If societies arise out of the cooperation of individuals and if, as is clearly the case, a society is a system of continuing cooperation, it follows that the study of society must deal with subjective phenomena. Why do men cooperate? What choices do they make in their cooperation? What ideas do they have about the scope of cooperation, about the resources available to them to satisfy their wants, about the reactions of each other to what they do, that induce them to make their choices? How do these choices interact to produce a social result? These are the questions which pose themselves for the social scientist. The objectivist cannot answer them, partly because he wishes them away, and partly because he denies himself the introspection which would enable him to see, from his knowledge of his own choices in action, why other men make choices and act upon them.”

“By its nature, objectivism erects measurability as the test of what is to be studied… But as a society is not a system of quantities but a system of relationships, its essentials cannot be measured… Measurement for the sake of measurement is worthless, and measurement of misleading or meaningless quantities may be worse than worthless.”

“Now, however, we must face a problem which Hayek’s Scientism did not deal with, namely the question of the legitimacy or virtue of macroeconomics. Is not the whole of macroeconomics infected with the collectivism that Hayek condemns? In concerning itself with the ‘economies’ of political entities, does it not treat them illegitimately as wholes? Are not the GNP, the national income, the general price level, etc. typical holistic fictions?”

“Macroeconomics can have value, but only in the hands of those who are first and foremost microeconomists.”

Ronald Max Hartwell – Liberal vs. Classical Liberal

Hayek uses the word liberal “in the classical sense of referring to the freedom of the individual from coercion by the state and other power groups. Hence it means opposition to government intervention, and, therefore, the opposite of the modern American meaning of the word as favoring or demanding government interventions.” Consequently, the contemporary term used by free-market advocates is classical liberal.

“Whereas capitalism is seen realistically with all its faults, socialism is only vaguely specified; socialism exists rather as an ideal, not as a system that has been tried and proved workable, not as a system whose virtues and vices have been compared realistically with capitalism. To compare the real faults of a system that is known with the alleged virtues of something not yet known, however, is to tilt the balance of approval decisively against the known. To use such a comparison as the basis for policy is surely irrational and certainly irresponsible; at least it displays uncalculating optimism.”

Shirley Robin Letwin – Economists and Politicians

“Hayek is not advocating an eternal ban against political talk by economists, but a recognition of the proper relation between abstract understanding and practical decisions. The distinction between them is essential to liberalism, which springs from a respect for concrete knowledge. An abstract theory cannot be used for deciding political issues without determining what conditions in the real world ‘correspond’ to the theoretical scheme. And this, Hayek points out, is often more difficult than understanding the theory itself. It requires a skill rather different from the economist’s, ‘something like a sense for the physiognomy of events.’ Therefore, while economic theory can tell us a great deal about ‘the effectiveness of different kinds of economic systems,’ it has ‘comparatively little to say on the concrete effects of particular measures in given circumstances.’”

“By the same token the politician who speaks as an economist fails at his job. The politician’s concern is with what is practicable in the existing state of opinion. He will be irresponsible and dangerous if he pursues policies without any sense for their relation to more general beliefs about what is possible and desirable. But if he commits himself to policies as if they were laws of nature, he may as easily be destructive and he is certain to become obsolescent.” See also The Overton Window.

“For all that Hayek has said about the virtues of the market as a spontaneous order, he has taken just as great pains to dispose of the fantasy of ‘laissez-faire’ conjured up by that ‘invisible hand’ and to explain that the ‘spontaneous order’ of the market is not a mechanical process given by nature.”

“One of Hayek’s greatest contributions to the defense of liberty is his repeated assertion that belief in the free market and competition, far from absolving us of having to think of legal arrangements, obliges us to do so more carefully… And when we are thinking about deliberate arrangements, we cannot, Hayek emphasizes, escape decisions about what is ‘just.’ The rule of law, as Hayek understands it, does not consist merely in a set of rules; it is a system of just rules.”

Some of the ideas in this book remind of topics written about by Thomas Sowell in later years, such as Knowledge and Decisions (1996) and Intellectuals and Society (2012).

Machlup, Fritz (editor), William F. Buckley Jr., Gottfried Dietze, Milton Friedman, Ronald Max Hartwell, Shirley Robin Letwin, George C. Roche III, Arthur Shenfield. Essays on Hayek. New York: New York University Press, 1976. Buy from Amazon.com

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Related Reading

Individualism and Economic Order by Friedrich Hayek (originally published in 1930s-1940s)

Collectivist Economic Planning, edited by Friedrich Hayek with essays by Ludwig von Mises, N.G. Pierson, George Halm, and Enrico Barone (originally published 1935)

The Road to Serfdom by Friedrich Hayek (1944)

Economics in One Lesson by Henry Hazlitt (originally published in 1946)

Intellectuals and Socialism (1949) described by William F. Buckley Jr.as “something of an afterword to The Road to Serfdom, which it properly is, I think.”

Capitalism and the Historians edited by Friedrich Hayek with essays by T. S. Ashton, Louis Hacker, W. H. Hutt, Bertrand de Jouvenel, (1954)

The Constitution of Liberty Friedrich Hayek (1960)

Law, Legislation, and Liberty by Friedrich Hayek (1973)

The Essence of Hayek edited by Kurt R. Leube and Chiaki Nishiyana (1984)

Warning to the West by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1986)

The Trend of Economic Thinking, Volume 3: The Collected Works of Friedrich Hayek, edited by W. W. Bartley III and Stephen Kresge (1991)

The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism by Friedrich Hayek, edited by W. W. Bartley III (1991)

Prices and Production and Other Works On Money, the Business Cycle, and the Gold Standard by Friedrich Hayek, edited by Joseph T. Salerno (2008)

Basic Economics Hardcover by Thomas Sowell (Fifth Edition, 2014)

The Austrian Theory of the Trade Cycle edited by Richard M. Ebeling with essays from F.A. Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, Murray Rothbard, Gottfried Haberler, and Roger Garrison (2014)

Studies on the Abuse and Decline of Reason by Friedrich Hayek, edited by Bruce Caldwell (2018). Includes the essay Scientism and the Study of Society, originally published as installments in the journal Economica, 1942-1944.

Discover more from The Key Point

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.