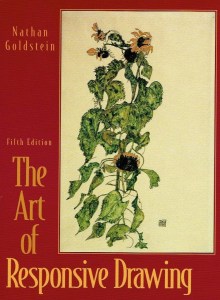

The Art of Responsive Drawing

by Nathan Goldstein (1927-2013)

I was prompted to read this book after a discussion with an art professor about what makes a work of art compelling. I commented that spontaneous gesture drawings can capture an intangible quality—energy, attitude, spirit—that is often lost in more technically resolved drawings and paintings. How does an artist preserve the initial spark of interest in a more complete work?

Nathan Goldstein writes about the expressive character of a drawing—that is to say, its psychological appeal grounded by the fundamentals of representational drawing: gesture, shape, line, value, perspective and foreshortening, volume, color, and composition.

“The best drawings always disclose a blend of facts and feelings, and to displace intuition and empathy with a dry intellectual examination of a subject’s structural condition upsets the necessary and delicate balance between discipline and indulgence that gives master drawings their individual character and spirit.”

Continue reading “The Art of Responsive Drawing”