Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World

by General Stanley McChrystal with Tantum Collins, David Silverman, and Chris Fussell

When General Stanley McChrystal took command of the Joint Special Operations Task Force in 2003, he was fighting a 21st-century war with a 20th-century military. This engaging book is about the reconfiguration which led to faster decisions and greater results. McChrystal’s mission was to defeat Al Quaeda in Iraq (AQI), but his leadership insights are applicable to business as well.

“AQI displayed a shape-shifting quality. It wasn’t the biggest or the strongest, but… AQI was a daunting foe because it could transform itself at will… Managerially, AQI was flanking us.”

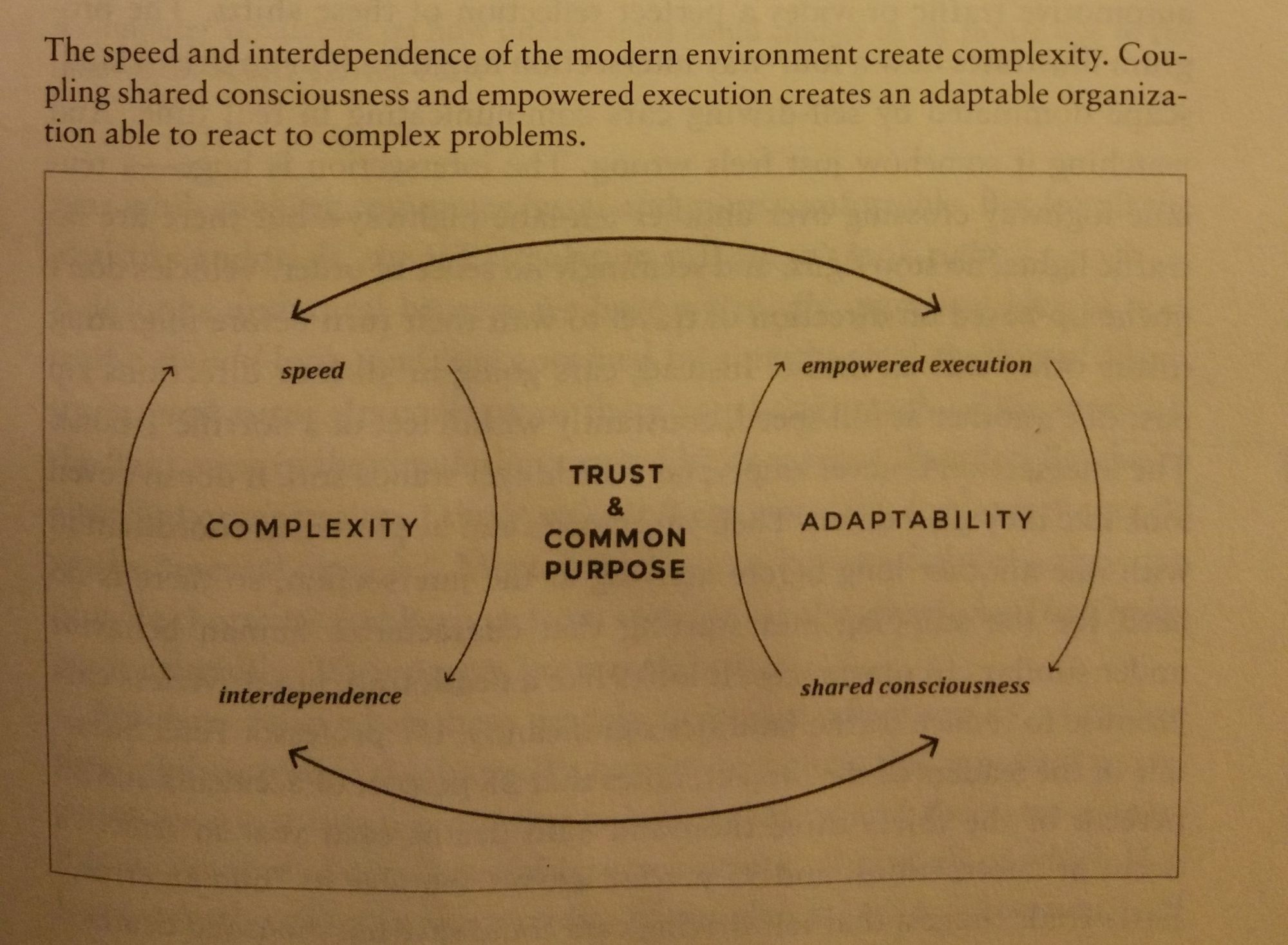

The enemy was a complex network. “Complexity… occurs when the number of interactions between components increases dramatically—the interdependencies that allow viruses and bank runs to spread; this is where things quickly become unpredictable.”

McChrystal realized, “Adaptability, not efficiency, must become our central competency… We were stronger, more efficient, more robust. But AQI was agile and resilient. In complex environments, resilience often spells success, while even the most brilliantly engineered fixed solutions are often insufficient or counterproductive… Resilience thinking is the inverse of predictive hubris. It is based in a humble willingness to know what we don’t know and expect the unexpected—old tropes that often receive lip service but are usually disregarded in favor of optimization.”

The U.S. military had very effective teams, such as Navy SEALs and Army Rangers. But “meaningful relationships between teams were nonexistent. And our teams had very provincial definitions of purpose: completing a mission or finishing intel analysis, rather than defeating AQI… Stratification and silos were hardwired throughout the Task Force… The blinks were even worse between the Task Force and our partner organizations: the CIA, FBI, NSA, and conventional military with whom we had to coordinate operations.”

“Our goal was not the creation of one massive team. We needed to create a team of teams. It may sound like a kitschy semantic distinction, but it actually marked a critical structural difference that turned the aspiration of scaling the magic of the team into a realizable goal… On a single team, every individual needs to know every other individual in order to build trust… But on a team of teams, every individual does not have to have a relationship with every other individual… We needed the SEALs to trust Army Special Forces, and for them to trust the CIA, and for them all to be bound by a sense of common purpose: winning the war, rather than outperforming the other unit. And that could be effectively accomplished through representation.”

“As interfaces became increasingly important, we realized the potential for bolstering our relationships with our partner agencies by way of a strong linchpin liaison officer (LNO). As it turned out, some of our best LNOs were also some of our best leaders on the battlefield… Our goal was twofold. First, we wanted to get a better sense of how the war looked from our partners’ perspectives to enhance our understanding of the fight… Second, we hoped that if the liaisons we sent contributed real value to our partners’ operations, it would lay a foundation for the trusting relationships we needed to develop between the nodes of our network. We became LNO fanatics. I would spend hours with my commanders hand selecting the best personalities and skill sets for different jobs… When they understood the whole picture, they began to trust colleagues.”

McChrystal implemented a profound shift from a need-to-know mindset to a culture of information sharing. “The problem is that the logic ‘need to know’ depends on the assumption that somebody… actually knows who does and does not need to know which material… Our experience showed us this was never the case… Functioning safely in an interdependent environment requires that every team possess a holistic understanding of the interaction between all the moving parts. Everyone has to see the system in its entirety for the plan to work… We did not want all the teams to become generalists—SEALs are better at what they do than intel analysts would be and vice versa. Diverse specialized abilities are essential. We wanted to fuse generalized awareness with specialized expertise… We dubbed this goal—this state of emergent, adaptive organizational intelligence—shared consciousness, and it became the cornerstone of our transformation.”

“Trust and purpose are inefficient: getting to know your colleagues intimately and acquiring a whole-system overview are big time sinks; the sharing of responsibilities generates redundancy. But this overlap and redundancy—these inefficiencies—are precisely what imbues teams with high-level adaptability and efficacy. Great teams are less like ‘awesome machines’ than awesome organisms.”

“The most critical element of our transformation… was our Operations and Intelligence brief…When I assumed command in 2003, the O&I was a relatively small video teleconference between our rear headquarters at Fort Bragg, a few D.C. offices, and our biggest bases in Iraq and Afghanistan… We urged everyone from regional embassies to FBI field offices to install secure communications so that they could participate in our discussions… Eventually we had 7,000 people attending almost daily for up to two hours. To some management theorists, that sounds like a nightmare of inefficiency, but the information that was shared in the O&I was so rich, so timely, and so pertinent to the fight, no one wanted to miss it.”

“The O&I also became one of the best leadership tools in my arsenal. Our organization was globally dispersed and included thousands of individuals from organizations not directly under the control of the Task Force. The O&I could not replace a hand on the shoulder, but video could convey a lot of meaning and motivation. Our leadership learned, over time, to use this forum not as a stereotypical military briefing where junior personnel give nicely rehearsed updates and hope for no questions. Instead, it was an interactive discussion. If an individual had a four-minute slot, the ‘update’ portion would be covered in the first 60 seconds, and the remainder of the time would be filled with open-ended conversation between the briefer and senior leadership (and potentially anyone else on the network, if they saw a critical point to be made)… Most important, it allowed all members of the organization to see problems being solved in real time and to understand the perspective of the senior leadership team. This gave them the skills and confidence to solve their own similar problems without the need for further guidance and clarification.”

“The fusion of operations and intelligence (O and I) was the essence of the meeting… The best moments in the O&I were when the briefing touched off a debate between different agencies, or teams, or departments. Perhaps two analytical silos had reached drastically different conclusions based on the same evidence, and we need to reconcile them and understand why.”

“The costs of micromanagement are increasing… I began to reconsider the nature of my role as a leader. The wait for my approval was not resulting in any better decisions, and our priority should be reaching the best possible decision that could be made in a time frame that allowed it to be relevant… I communicated across the command my thought process on decisions like airstrikes, and told them to make the call… Decisions came more quickly, critical in a fight where speed was essential to capturing enemies and preventing attacks. More important, and more surprising, we found that, even as speed increased and we pushed authority down further, the quality of decisions actually went up.”

The results were impressive. Under the old structure, there were 10 to 18 raids per month. “By 2006, under the new system, this figure skyrocketed to 300. With minimal increases in personnel and funding, we were running 17 times faster. And these raids were more successful. We were finding a higher percentage of our targets, due in large part to the fact that we were finally moving as fast as AQI, but also because of the increased quality of decision making.”

“The term empowerment gets thrown around a great deal in the management world, but the truth is that simply taking off constraints is a dangerous move. It should be done only if the recipients of newfound authority have the necessary sense of perspective to act on it wisely.” In other words, “Empowered execution without shared consciousness is dangerous.”

McChrystal writes about leadership by example. “As a young officer I had been taught that a leader’s example was always on view. Bad examples resonate even more powerfully than good ones… I sought to maintain a consistent example and message… The O&I served as my most effective leadership tool as well, because it offered me a stage on which to demonstrate the culture I sought… I was on live TV in front of my entire force and countless interagency partners every day for an hour and a half. If I looked bored or was seen sending e-mails or talking, I signaled a lack of interest… Critical words were magnified in impact and could be crushing to a young member of the force… ‘Thank you’ became my most important phrase, interest and enthusiasm my most powerful behaviors.”

I am impressed by the general’s sense of empathy. “Over my career I’d watched senior leader visits have unintended negative consequences. Typically schedules were unrealistically overloaded and were modified during the visit to cancel parts of the plan… Invariably soldiers who had spent days preparing a briefing or demonstration for the great man’s visit were informed at the last minute that all of their work had been for naught. It was not a good way to improve morale… I would tell my staff about the dinosaur’s tail: As a leader grows more senior, his bulk and tail become huge, but like the brontosaurus, his brain remains modestly small. When plans are changed and the huge beast turns, its tail often thoughtlessly knocks over people and things. That the destruction was unintentional doesn’t make it any better.”

“Creating and leading a truly adaptive organization requires building, leading, and maintaining a culture that is flexible but also durable. The primary responsibility of the new leader is to maintain a holistic, big-picture view, avoiding a reductionist approach, no matter how tempting micromanaging may be… The leader’s first responsibility is to the whole.”

“Shared consciousness is a carefully maintained set of centralized forums for bringing people together. Empowered execution is a radically decentralized system for pushing authority out to the edges of the organization. Together, with these as the beating heart of our transformation, we became a single, cohesive unit far more agile than its size would suggest… The Task Force still had ranks and each member was still assigned a particular team and sub-sub-command, but we all understood that we were now part of a network; when we visualized our own force on the whiteboard, it now took the form of webs and nodes, not tiers and silos… To defeat a network, we had become a network. We had become a team of teams.”

I highly recommend this book along with another book on managing complexity in a business context: It’s Not Complicated: The Art and Science of Complexity in Business by Rick Nason.

McChrystal, Stanley A., Tantum Collins, David Silverman, and Chris Fussell. Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. New York: Portfolio / Penguin, 2015. Buy from Amazon.com

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

10 thoughts on “Team of Teams”

Comments are closed.